The following post displays my research, review, and report on federal permits for plants listed on the Endangered Species Act. It took me years to gather the information, process the information, have it reviewed, then send for submission to a paper, then rejected. It wasn't rejected on facts, rather other reasons that I may post later, but to summarize, not the scope of the journal or made no point etc. The process to is complex, challenging, and can be frustrating. I didn't post this before as I evaluated myself as a "frustrated" state if I felt it or not. Now years later, I believe it is still useful information, so I post it here. I've "censored" what I call it, personal information such as names of people that helped me, such as reviewers. Figure 2 and image posted first for thumbnail code attempt as a function of Blogger Blog. There is a lot to this story and I will post stuff when I find it.

censored – censored

15 February 2017 Version 23 Last Edited 6 April 2017

Keywords: Endangered Species Act, Endangered Species Map, Fish and Wildlife Service, Habitat Conservation Plan, Interstate Commerce Permit, Scientific Permit

Keywords Selected: Endangered Species Act, Fish and Wildlife Service, Conservation Planning, Plants, Politics and Policy, Threatened Species

Acknowledgments

I thank censored, censored, and censored for reviewing the document, as well as the United States Fish and Wildlife Service and United States Department of Agriculture for discussions on the subject.

Recovery Permits of Federally Endangered and Threatened Plants of the United States

Running Head: Recovery Permits of Plants

Abstract

Many activities involving protected plants are prohibited by the regulations of the Endangered Species Act of the United States except when permitted for recovery projects. The following review reports on the status of plant species recovery nationally through an examination of federal permits from 1994 to 2015. Despite the additional listing of hundreds of plant species, the number of permits requested (less than 29 per year) and issued (less than 6 per year) was consistently low. Moreover, most of the 883 listed plants reviewed had few to no permit requests. Removal of plant or plant parts from the wild for research or mitigation accounted for most requests (82%). Although every state had at least one federally listed plant species, the distribution of permit requests differed among regions of the country. Unless changes that encourage public involvement are made, endangered and threatened plant species cannot be expected to recover.

Introduction

Between 1977 and 2015, there have been 898 plants listed as federally endangered and threatened in the United States (Greenwalt 1977; United States Fish and Wildlife Service, further referenced as FWS, 2015, FWS 2016a). Human activities through land modification and utilization of the environment have driven many plant species to near extinction (Czech et al. 2000; Lawler et al. 2002; FWS 2003). In response to this threat to biodiversity, the Endangered Species Act (FWS 2003) established regulations intending to protect, recover, and restrict activities involving such species (Czech et al. 2000; Lawler et al. 2002; Schwartz 2008). However since the protections were enacted, only 16 plant species have recovered (FWS 2016a). A review of recovery practices pertaining to the remaining plant species can provide insight to why so few plants are recovering.

Recovery programs of plant species can be examined through the FWS permitting system. The FWS issues a variety of permit types that allow people to engage in otherwise prohibited activities involving listed plants of the Endangered Species Act (FWS 2013; United States Government Publishing Office 2016). Such permits are issued only if the FWS determines that the proposed activities aid in plant recovery. Generally the regulations prohibit the collection and transfer of listed plants from the wild. Scientific permits allow research activities that include possessing, growing, surveying, and removing entire or parts of plants from the wild. Habitat conservation plan permits allow the destruction of plants when it cannot be avoided, as in the case of construction projects and the collection of natural resources such as mining or oil and gas operations. The FWS develops a cooperative agreement with habitat conservation plan applicants to mitigate the harm to listed plants. Also regulated by the Endangered Species Act are business activities such as buying and selling listed plants across state and country borders (FWS 2004). Interstate commerce permits allow movement of endangered species for commercial activities across states within the United States. Import and export permits regulate the movement of listed plants into and out of the United States.

This review intends to report on the status of the FWS permitting system for federally endangered and threatened plants. A variety of questions are addressed, such as: For what plant species and activities were permits requested? Who requested permits? When were permits requested? In addition, data pertaining to listing year and location of plants are also reported.

Methods

I started by compiling a list that contained common and scientific names, the lead FWS regional offices, and listing status as either endangered or threatened of plants (FWS 2015). Documents of endangered species permit requests, which can refer to plants that are threatened as well, are displayed on the Federal Register (www.federalregister.gov; example: Gould 2002), the federal publication of proposed and final regulations, as required by the Endangered Species Act Section 10. Exceptions (c) (FWS 2003). Using the word “permit” and the scientific name of each plant species, I searched within the Federal Register between February and May 2015 for permit requests. Search results revealed requests for permits as well as permits issued. The earliest documents of permit information found from the search refer to 24 March 1994. There may have been earlier permits requested, issued, amended, or posted, but they were not found through online searches of the Federal Register and were not evaluated. A single permit may be requested multiple times to modify the expiration date, permitted activity, applicant information, or to add or remove permitted species. Therefore I used the permit number and date to determine the first dated entry (considered new) and subsequent amendments of permit requests. I used applicant names and titles to uniquely identify and categorize applicants. The state residencies of applicants were used to determine the location of requested permits.

To determine what activities are requested, I categorized the type of permit requested. I separated “scientific” permits into two categories for analysis, “reduce and remove to possess” and “presence-absence surveys.” This was done to distinguish between activities of plant removal from the wild and those where plants were solely observed. In total I examined permit types within 6 categories: reduce and remove to possess, presence-absence surveys, habitat conservation plan, interstate commerce, import, and export.

To determine who requested permits, I categorized permit applicants. Concordant with the federal endangered species permitting system and permitting officials, I categorized private (non-government) applicants with the label of “company” for applicants with an affiliation with a group and “individual” for applicants with no apparent membership association. A category was designated for university affiliation given that universities could be considered both government or privately regulated. In total I categorized applicants as federal (federal agencies including the military), state (issued to state, county, or city agencies), university (including associated herbarium, botanical gardens, museums), company (both for and non-profit organizations), and individual (a single name with no evidence to suggest that it belongs in any of the previous categories).

A permit can include activities involving a single or multiple plant species. In response, I examined plant species within each permit. I used the term “permission” to describe the request of individual species within permits.

To determine when permits were requested, I evaluated the listing date of plant species (FWS 2016b) and the date of permit applications. Excluding the partial years (1994 and 2015), I performed one-way analysis of variance of requested permits within 5 year intervals to determine change in permit requests (Lakens 2013; McDonald 2014). The analysis of variance was similarly performed for permissions.

I displayed the location of plant species (FWS 2015, 2016b) and permit requests in maps using ArcGIS 10.2. Plant species are assigned to FWS regional offices (FWS 2016d) with exceptions that include international species, species found across multiple regions, and Johnson's seagrass (Halophila johnsonii) which is assigned to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. The assigned regional office of the species handles most permit requests for that plant (FWS 2016d). The national headquarters of the FWS handles interstate commerce, import, and export permit requests with input from regional offices. Data were omitted if the applicant did not have an address in the United States (such as applicants from Canada and the United Kingdom). Attempts were made to divide permits that covered multiple states but were omitted since not all of the species requested on the permits were found in all of the listed states. Multi-state permits appeared to cover possible unintended activities rather than the direct involvement with plants. I averaged the number of permissions requests per plant to compare regional offices of the FWS.

Recovery activities would lack representation by requested permits if actual issued permits were not examined and explained. Obtaining permit information by contacting the FWS directly was costly, discouraged, in some cases impossible, and therefore not performed. The Federal Register contains posts of issued permits as required by the Endangered Species Act Section 10. Exceptions (d) (FWS 2003). Posts of issued permits have a similar format which include the permit number, applicant, and sometimes the issuance and expiration date; yet the format may vary, and information may have changed from the original application request. I searched within the Federal Register for documents of issued permits using the word endangered and the permit number of each permit. I then searched the titles of those returned documents to find additional information of issued permits.

Results

I located over 700 documents in the Federal Register that contained permit information for the 883 plant species (725 endangered and 158 threatened). Before 24 March 1994, 15 plant species had been removed from the endangered and threatened species list (FWS 2016a) and were not included in this review. There were 608 permit requests, including 454 (75%) new permit requests and 154 (25%) amendments to existing requests. Most permits were requested once (80%) and none more than six times except for a FWS Region 1 permit which was requested 21 times. More than half of all permit requests included coverage of multiple (56%) rather than a single (44%) plant species. FWS Region 1 requested coverage of 190 plant species, the most of any permit applicant. Most plant species had few or no permit requests (51% of plant species with 1-5 requests; 30% without requests), and few were frequently requested (6-27 requests, 19%).

Most permit requests involved removing plants or plant parts from the wild (70% reduce and remove to possess and 12% habitat conservation plan). Another 14% requested surveying plants. Few requests (4%) were for movement permits; interstate commerce, import, and export.

There were 454 permit applications that requested 2670 permissions to engage in activities for plant recovery (Table 1). Government agencies requested nearly a third of permits and nearly half of permissions. Non-government entities requested over half of permits and nearly half of permissions. Universities had the fewest requests. Federal agencies averaged the most plant species per permit (10.4), whereas other categories averaged fewer (6.4 or less).

Between 1977 and 1989, 24% of the plant species evaluated were listed, over half (57%) between 1990 and 1999, and almost one fifth (19%) since 2000. At least one new plant species has been added to the endangered and threatened species list every year since 1977 except for a 4 year span between 2005 and 2008 when no plants were added. Differences in species listing are attributed to political circumstances and funding allocation (Stinchcombe 2000). During the 21 years of documents reviewed (24 March 1994 to 6 April 2015), an average of 20.7 plant species were added to the endangered and threatened species list annually totaling 434 (49%) of the 883 species reviewed.

The number of new plant species added to the endangered and threatened species list is close to that of new permit requests. Excluding the partial years of 1994 and 2015, there were, on average, 21.8 new permits and 7.1 amendments to existing permits (28.9 total), and 124.6 permissions requested per year. When permit requests were divided evenly among regions, FWS offices receive very few (3.6) permit requests for plants per year.

The number of permits requested has remained consistent across 20 years as no statistical difference was found when permit requests were grouped into 5 year intervals (F value=2.694, DF [3, 16], p=0.08, η2p=0.336, 90% CI [0, 0.488]). Similarly with no statistical differences, permission requests have also remained consistent when grouped in the same fashion (F value=1.642, DF [3, 16], p=0.219, η2p= 0.235, 90% CI [0, 0.394]). Within 5 year intervals, the percentage of requested amendments of total permits from 1995-1999 was 14%, this increased to 21-22% for 2000-2009, and continued to rise to 35% for 2010-2014.

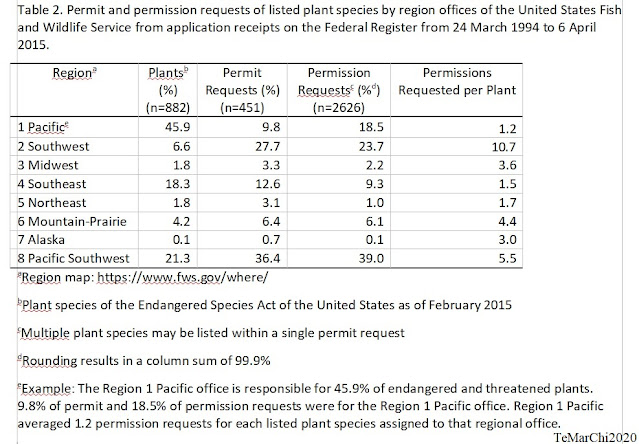

The distribution of permit requests does not reflect the distribution of species, and these differ among FWS regional offices (Table 2). Every state has a listed plant species (Figure 1), yet no permits were requested for 12 states (Figure 2). FWS region 1, contains nearly half of all listed plant species yet has few permit and permission requests. Region 1, which includes Hawaii, the state with the most listed plant species, lacks permit and permission requests to cover all species within that region. Region 4 also contains a high number of species with low permit and permission requests. Combined FWS region 2 and region 8 contain nearly 28% of species and over 60% of permit and permission requests. On average, region 2 has the highest amount of permission requests per species at nearly double that of any other FWS region. Combined region 1 and region 4 contain 64% of all plant species and have the least permissions requests per species at less than a fifth of that compared to region 2.

Federal Register documents indicate few (24%) permit applications granted a permit (Table 1). Application requests that lacked a permit number (19%), most often requests for habitat conservation plan permits, were assigned a place holder value which made them invalid for issuance determination. No information was found to determine the outcome for the remaining 57% of requested permits. Compared to permits, a higher percentage of permissions were determined as granted (40%, Table 1) indicating granted permits allow for work with a high number of species per permit.

Discussion

The number of permits requested to engage in federally regulated activities involving the recovery of endangered and threatened plants has remained consistently low over the past 20 years. The current threats to rare plants will continue to push these species and others toward extinction, and more species will qualify for listing as a result (Boersma et al. 2001). Consequently an increasing amount of effort will be needed to study and recover these plant species. However if permit applications and permission for existing species are any indication, endangered and threatened plant species cannot be expected to recover because so few people are attempting to request permits.

Johnston's frankenia (Frankenia johnstonii) was the 16th plant removed from the list of the Endangered Species Act (Guertin 2016; FWS 2016a). This review found Frankenia johnstonii had 13 permits requested (36th most out of the 883 total species) and had at least 7 permits issued (17th most out of the 883 total species). The FWS credits the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, a permit holder, as performing “primary conservation actions” which led to delisting the species (Guertin 2016). Frankenia johnstonii would not have been delisted without the aid of permits holders. The FWS should encourage permit requests from entities that can aid in the recovery and delisting of plant species.

Permits to work with endangered plants are requested only if there is sufficient interest in these species and their recovery. Support from the public is one of the goals of the Endangered Species Act and is a critical aspect of recovering listed species. Unfortunately, the current permitting system of the FWS has effectively discouraged permit requests (Rogers 1999) for the past two decades. Applying for an endangered species permit is complex, and obtaining information is challenging. Yet no guideline exists explaining to potential applicants the appropriate way in which to apply for a permit or how permit applications are reviewed, issued, or rejected. Consequently, many permit applications likely fail simply because they were completed incorrectly by the applicant. Finding out who to contact with questions about the application process is also difficult (Rogers 1999). When the appropriate FWS personnel are contacted concerning permits, they often do not provide complete or consistent answers or consultation is unavailable (Rogers 1999). A non-public database system called the “Service Permit Issuance and Tracking System” was created by the FWS to improve efficiency and correct problems in the permitting process (Rogers 1999), yet there has been no increase in permit requests for plants after its creation 16 years ago. Applying for a permit is time consuming (Rogers 1999) and monetarily costly (FWS 2016c). It can take years and cost hundreds of dollars to applicants to submit and wait for the processing of their application. Although these obstacles do filter out non-serious applicants, they appear to be too complex and likely prevent many serious applicants that could do valuable work in the recovery of endangered species.

Many endangered species permits are requested by and issued to the FWS and their partners. FWS partners include other federal agencies, cooperating state agencies, universities whose research is funded by the government, and businesses with federal contracts to perform work related to endangered and threatened plant species. Some FWS regional offices apply and self-issue permits through their own office (Gould 2002). State agencies often requested federal permits for intrastate activities. Such state programs are overseen and provided federal support, including funding through the FWS, for their own endangered species programs (Endangered Species Act Sec. 6 Cooperation with the States [d], FWS 2003). Therefore the number of permits requested by and issued to government agencies and their affiliates is likely underestimated by this review since it was not possible to accurately determine the true nature of every applicant based on the information in the Federal Register.

The FWS appears to prioritize on government, rather than non-government, permit applicants. The FWS builds a working relationship with government applicants helping them through the permitting process which results in issued permits (Endangered Species Act Sec. 7 Interagency Cooperation, FWS 2003). This type of working relationship is not outlined for non-government entities. The FWS takes its first action with non-government applicants after the application has been submitted. Applications may be rejected by the FWS due to lack of information whether the applications are completed or not. Applications are then terminated if additional materials are not submitted within 45 days. These obstacles may be avoided if the FWS and non-government agencies were to communicate before and after application submission. Without the opportunity of such communication, the FWS effectively restricts the ability of non-government entities to assist with the recovery of endangered and threatened plant species.

Many of these problems are may be partially attributed to FWS permitting offices being understaffed and underfunded (Miller et al. 2002; Schwartz 2008). FWS staff are difficult to contact because there are so few for the workload (Schwartz 2008), and funds may not permit the hiring of additional personnel (Schwartz 2008). Without a change in public support for additional funding, these restraints will likely continue, and the FWS may need to plan accordingly. The FWS may have to convert from performing recovery activities to monitoring entities that have the funds, manpower, and other characteristics that result in the ability to recover listed species. Such entities include local governments, educational institutions, conservation societies, environmental organizations, nonprofit and for profit companies, scientists, hobbyists, other groups, and individuals. These entities have been shown to improve endangered species recovery (Boersma et al. 2001), but are, at this time, underutilized. The recovery of plant species will require more public involvement (Hollander 1972; O’Brien 1993; Bailey 2011). Public involvement can be encouraged if the FWS assists interested parties with the application process, which should result in more successful applications and permits issued. The FWS could then focus on monitoring these entities to insure they are held accountable, and are not themselves detrimental to the plant species.

Currently the public can review and submit comments to the FWS regarding pending permit applications displayed on the Federal Register. Public review provides an opportunity to present new information to the FWS. Acceptance of public information validates the FWS has examined all sources of information before granting a permit. Although most entries on the Federal Register have a similar format, there are no guidelines as to which permit information must be displayed. Some entries lack basic information such the species (Oetker 2014) or the scientific name of the species (Pultz & Rabot 2010) for which the permit applies. Taxonomic re-classification creates another problem (Guertin 2015) because information associated with the previous name of the species is lost when plant names are changed. Some documents for plant species with changed names were found in this review, yet others may have been missed. Perhaps a unique identifier number should be assigned to each species when listed. Due to the low percentage of granted compared to requested permits, it appears most permits are not granted. In response, I contacted applicants and confirmed they were granted a permit, yet could not find that information in the Federal Register. This would suggest that not every permit request, issuance, and amendment are published in the Federal Register or a more complex search for that information is required. Without the availability of this information an expert on the species may not know to comment, new information cannot be presented, and the FWS fails to meet its targeted audience for which permit information is posted on the federal register.

This review does not cover all recovery activities of endangered and threatened plants. Certain activities pertaining to threatened plant species do not require a permit or Federal Register entry, yet many are still posted on the Federal Register. Federal permits are required for activities on federal lands or to cross state lines, but often are not required for intrastate activities on non-federal property. Most states have their own state endangered species act, laws, and personnel that enforce regulations similar to the federal act (Goble et al. 1999), yet were not reviewed and are not as accessible to the public. Intrastate activities may explain why states, such as Hawaii, with a high number of endangered and threatened plants have a low number of permit requests. Intrastate activities may also explain why requests were low from universities. Although some recovery activities do not require a federal permit, they are still few, and more help will be required to recover plant species at risk of extinction.

This review can provide insight to future applicants of the process of obtaining a federal permit to engage in endangered and threatened plant recovery activities as well as provide feedback to the FWS on how their current system has limits for the recovery of listed plant species. The problems with the permitting system explored in this review are not new, but until now there were no statistics to demonstrate these issues. Through identification of the problems, solutions can be created. Furthermore, methods similar to those employed by this review could be used to analyze other aspects of the endangered and threatened species permitting system. A future review could reveal a bias in the permitting system as scientific research (Clark & May 2002) and government activities (Czech et al. 1998; Gerber & Shultz 2001; Negron-Ortiz 2014) often focus on specific organism groups, typically towards birds and mammals, and often neglect plants. To recover plant species that are approaching extinction, more of the public will have to engage the FWS, and the FWS will have to provide the public more opportunities to help in the recovery process.

Literature Cited

Bailey T. 2011. The dummies guide to promoting wildlife conservation in the Middle East: telling tales of unicorns and ossifrages to save the hawk and leopard. Journal of Avian Medicine and Surgery 25(2):136-143.

Boersma P, P Kareiva, W Fagan, J Clark, J Hoekstra. 2001. How good are endangered species recovery plans? BioScience 51(8):643-649.

Clark J, R May. 2002. Taxonomic bias in conservation research. Science 297(5579):191-192.

Czech B, P Krausman, R Borkhataria. 1998. Social construction, political power, and the allocation of benefits to endangered species. Conservation Biology 12(5):1103-1112.

Czech B, P Krausman, P Devers. 2000. Economic associations among causes of species endangerment in the United States. BioScience 50(7):593-601.

Gerber L, C Schultz. 2001. Authorship and the use of biological information in endangered species recovery plans. Conservation Biology 15(5):1308-1314.

Goble D, S George, K Mazaika, J Scott, J Karl. 1999. Local and national protection of endangered species: an assessment. Environmental Science & Policy 2(1):43-59.

Gould R. 2002. Notice of receipt of applications for endangered species recovery permit. Federal Register, Washington, District of Columbia. Available from https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2002-05-30/pdf/02-13421.pdf (accessed April 2015).

Greenwalt L. 1977. Determination that seven California Channel Island animals and plants are either endangered species or threatened. Federal Register, Washington, District of Columbia. Available from https://www.fws.gov/carlsbad/SpeciesStatusList/List/19770811_fList_Seven%20California%20Channel%20Island%20Animals%20and%20Plants.pdf (accessed November 2016).

Guertin, S. 2015. Endangered and threatened wildlife and plants; technical corrections for 54 wildlife and plant species on the list of endangered and threatened wildlife and plants. Federal Register, Washington, District of Columbia. Available from https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2015-06-23/pdf/2015-15212.pdf (accessed February 2017).

Guertin S. 2016. Endangered and threatened wildlife and plants; removal of Frankenia johnstonii (Johnston’s frankenia) from the federal List of endangered and threatened Plants. Federal Register, Washington, District of Columbia. Available from https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2016-01-12/pdf/2016-00158.pdf (accessed November 2016).

Hollander J. 1972. Scientists and the environment: new responsibilities. Ambio 1(3):116-119.

Lawler J, S Campbell, A Guerry, M Kolozsvary, R O’Connor, L Seward. 2002. The scope and treatment of threats in endangered species recovery plans. Ecological Applications 12(3):663-667.

Lakens D. 2013. Calculating and reporting effect sizes to facilitate cumulative science: a practical primer for t-tests and ANOVAs. Frontiers in Psychology 4:863.

McDonald J. 2014. One-way anova. Pages 146-157. Handbook of biological statistics. 3rd edition. Sparky House Publishing, Baltimore.

Miller J, M Scott, C Miller, L Waits. 2002. The Endangered Species Act: dollars and sense? BioScience 52(2):163-168.

O'Brien M. 1993. Being a scientist means taking sides. BioScience 43(10):706-708.

Oetker M. 2014. Receipt of applications for endangered species permits. Federal Register, Washington, District of Columbia. Available from https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2014-10-17/pdf/2014-24702.pdf (accessed November 2016).

Negron-Ortiz, Vivian. 2014. Pattern of expenditures for plant conservation under the endangered species act. Biological Conservation 171:36-43.

Pultz S, T Rabot. 2010. Proposed issuance of incidental take permits to the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife for state of Washington wildlife areas. Federal Register, Washington, District of Columbia. Available from https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2010-10-01/pdf/2010-24692.pdf (accessed November 2016).

Rogers J. 1999. Proposed policy on general conservation permits. Federal Register, Washington, District of Columbia. Available from https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-1999-10-28/pdf/99-28232.pdf (accessed November 2016).

Schwartz M. 2008. The performance of the Endangered Species Act. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 39:279-299.

Stinchcombe J. 2000. U.S. endangered species management: the influence of politics. Endangered Species UPDATE 17(6):118-121.

United States Fish and Wildlife Service. 2003. Endangered Species Act of 1973 as amended through the 108th congress. Washington, District of Columbia. Available from https://www.fws.gov/endangered/esa-library/pdf/ESAall.pdf (accessed February 2016).

United States Fish and Wildlife Service. 2004. 18 USC § 42-43 and 16 USC § 3371-3378 Lacey Act. Washington, District of Columbia. Available from https://www.fws.gov/le/pdffiles/Lacey.pdf (accessed February 2016).

United States Fish and Wildlife Service. 2013. Permits for native species under the Endangered Species Act. Arlington, Virginia. Available from http://www.fws.gov/ENDANGERED/esa-library/pdf/permits.pdf (accessed May 2016).

United States Fish and Wildlife Service. 2015. U.S. Species. Falls Church, Virginia. Available from http://www.fws.gov/endangered/species/us-species.html (accessed February 2015).

United States Fish and Wildlife Service. 2016a. Delisting report. Washington, District of Columbia. Available from http://ecos.fws.gov/tess_public/reports/delisting-report (accessed May 2016).

United States Fish and Wildlife Service. 2016b. Find Endangered Species. Washington, District of Columbia. Available from http://www.fws.gov/ENDANGERED/index.html (accessed May 2016).

United States Fish and Wildlife Service. 2016c. Forms. Washington, District of Columbia. Available from https://www.fws.gov/forms/display.cfm?number1=200 (accessed September 2016).

United States Fish and Wildlife Service. 2016d. No Title. Washington, District of Columbia. Available from https://www.fws.gov/where/ (accessed October 2016).

United States Government Publishing Office. 2016. Title 50: Wildlife and fisheries Part 13-gerneral permit procedures. Electronic Code of Federal Regulations, Washington, District of Columbia. Available from http://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/text-idx?SID=57a0f43415cf380da009a226b3bd6974&mc=true&node=pt50.1.13&rgn=div5#sp50.1.13.a (accessed November 2016).

Figure 2. Number of permits (n=451), and plants listed within those

permits (permissions, n=2626), requested as determined by addresses from

receipts of permit applications posted on the Federal Register of the

United States from 24 March 1994 to 6 April 2015. Note: Applicants may

request permissions of plants from another state. Foreign country, Fish

and Wildlife Service office of the District of Columbia, and multi-state

permit requests are not shown. Maps are of unequal scale. Alaska and

island locations are not exact. Example: 5 permits and 44 permissions

were requested on applications that listed an address from applicants of

Georgia.

Figure 1. Distribution of listed plant species of the United States Endangered Species Act as of February 2015 (n=883; a species may exist in multiple states). Note: Maps are of unequal scale. Alaska and island locations are not exact. Example: 18 endangered and 8 threatened plant species are found within Georgia.